Emperors and peasants

Peasant serfdom and Habsburg reformism in the 18th century

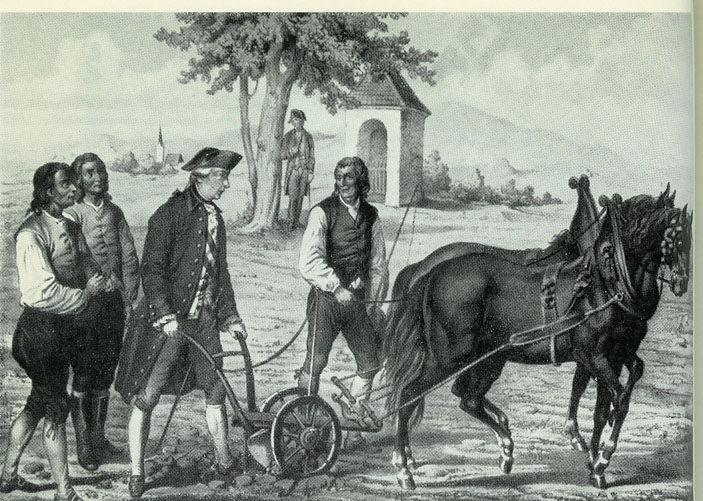

Nineteenth-century illustration depicting the future emperor Joseph II plowing a field. The scene refers to an episode that occurred in 1769 in Moravia, in the town of Slavìkovice. While waiting for his carriage to be repaired, the emperor helped the local farmers plow their field. - Commons Wikimedia.

Around the mid-1700s, millions of peasants in the Habsburg Empire lived under harsh conditions of servitude. In regions such as Bohemia, Hungary, Styria, and Galicia, peasants were required not only to pay rent but also to provide landowners with a portion of their harvest and free labor. This latter obligation often consumed up to three days a week, leaving peasants with little time to harvest their own grain or produce surpluses, making it increasingly difficult to pay rent to landlords and taxes to the state.

Furthermore, in some areas, peasants were unable to move, marry, or change professions without the landowner's consent. Complaints about injustices were often adjudicated by the very same local nobles, further entrenching inequality. From the latter half of the 18th century, the Habsburg dynasty began efforts to address these issues. The monarchs viewed this system as problematic not only from an ethical and moral perspective—strongly influenced by Enlightenment ideas—but also from a practical standpoint. Agricultural productivity and tax revenue from many rural regions were low, and soldiers recruited from the peasant population were weak and malnourished.

The crown sought to transform peasants into free individuals, ideally landowners working their own fields. Between 1760 and 1770, Maria Theresa attempted to curtail the privileges of landowning nobles, specifically aiming to replace peasants' labor obligations with monetary payments, which would be divided between the landlords and the state. Joseph II's reforms were far more radical. Between 1781 and 1784, through a series of decrees, he removed the barriers to peasants' personal freedom and also limited the landlords' authority to impose punishments and fines.

As a result, the peasant population began to see the Habsburgs as allies in their struggle against the abuses of their masters. Joseph II, in particular, became a popular hero in their eyes—especially after he personally plowed a field in Moravia in 1769. However, the final abolition of feudal constraints in the Austrian Empire would not occur until 1848.

Pieter M. Judson, L'impero asburgico. Una nuova storia, Keller publisher, 2021

2025-06-21

Salvatore Ciccarello